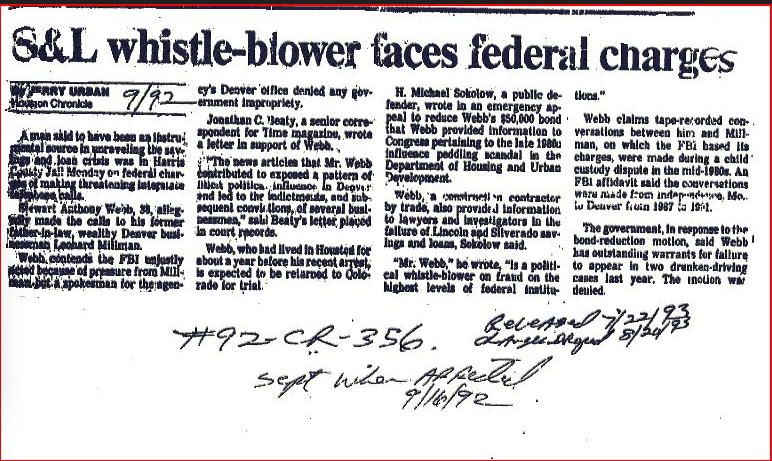

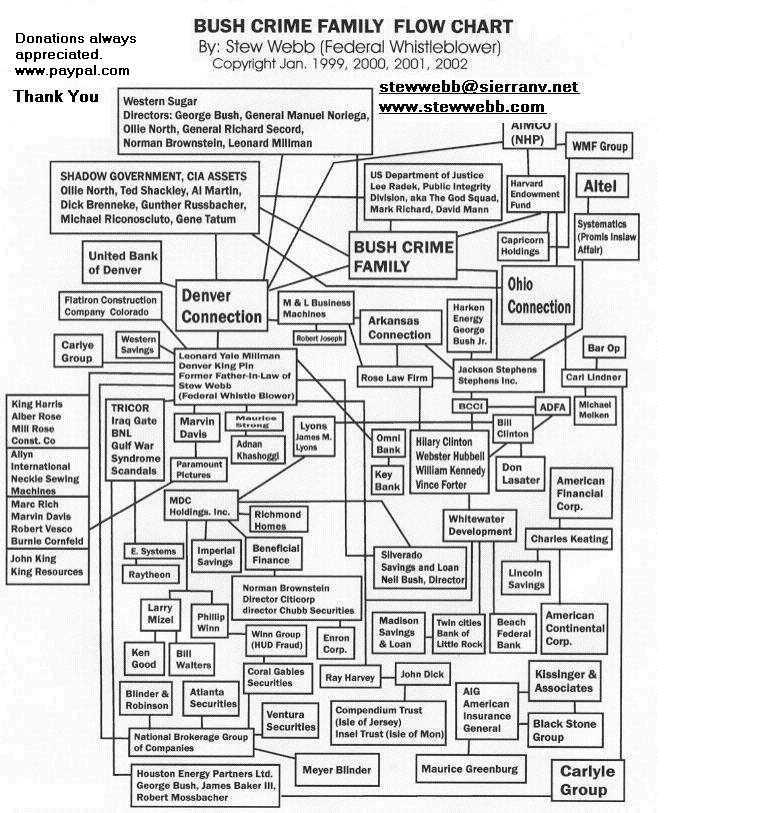

By Stew Webb

Inslaw the Prosecutors software sold by Bill Hamilton to the U.S. Justice Department in the 1980s that he was never paid and the software was used for the Bush Crime Syndicates sinister purposes.

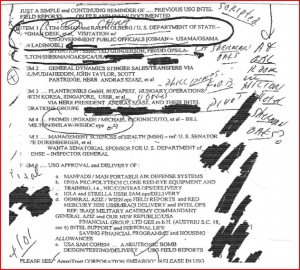

The documents and series of articles below, a U.S. Government internal memorandum show’s FBI Ted Gunderson’s involvement in Inslaw with Michael Riconosciuto. It further is proof of Ted Gunderson’s involvement with Osama bin Laden also known as CIA Asset Tim Osman selling Stinger Missiles to Afghanistan Rebels in the late 1970s for the Bush Organized Crime Syndicate.

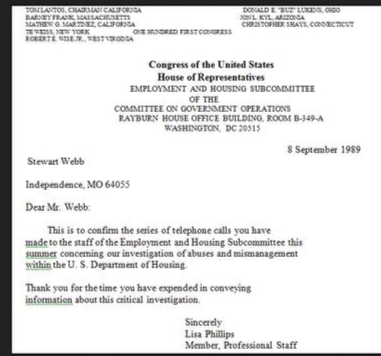

The articles below were written by Kelly O’Meara of Insight Magazine of the Washington Times, I had several discussions with Kelly (a great gal) during the time she wrote the articles.

Kelley stated “I have never done any articles that caused me so much heat”.

Ted Gunderson tried to persuade Kelly from writing any further articles to silence what CIA Michael Riconosciuto had to say.

Former US Custom Agent Jim Rothstein is very knowledgeable of Ted Gunderson’s Washington, D.C. child sex ring for George HW Bush and how Gunderson has illegally set up people and incarcerated them in behalf of the Government and the Bush Crime Syndicate.

Take Michael Riconosciuto who worked with Ted Gunderson out of the Bush CIA Cabazon Indian Reservation, changing the stolen Inslaw Promise Software by planting a trap back door in the software for the Bush Crime Syndicate. When Riconosciuto came public about what he had done, Ted Gunderson framed him up for the Bush Crime Syndicate and Michael has served 20 of a 24 illegal year prison term. ABC reporter Danny Casolaro after meeting with my good friend Bill McCoy was murdered in Fairfax, Virginia he was working on his book the Octopus. Bill McCoy whom I worked with from 1991-1997 until his murder, was a former Pentagon Investigator who worked many well known cases as a license Private Investigator. Bill was the Private Investigator for Bill Hamilton who designed and built the Inslaw Prosecutors software to track white collar criminal. Bill had hundreds of other famous clients such as Private Bill Tyree who sued exposing that Ollie North and George HW Bush created FEMA from Narcotics Laundered Money. Bill Tyre who is in prison for killing his wife that he never did do his wife was killed by the Bush Crime Syndicate to silence him and her. Ed Wilson who was involved in EATSCO was another client. Terry Reed, Leo Wanta, Gene Chip Tatum, Al Martin and the list goes on who Bill McCoy helped. Bill was murder for helping exposed the Oklahoma City Bombing in 1995 and the Israel involvement with The Bush Organized Crime Syndicate.

JAN 29, 2001

By Kelly Patricia O Meara

Good morning, Mr. McDade. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police has reason to believe that the national security of Canada has been compromised. A trojan horse, or back door, allegedly has been found in computer systems in the nation’s top law-enforcement and intelligence organizations.

“Your mission, should you decide to accept it, is to establish whether this is the PROMIS software reportedly stolen in the early 1980s from William and Nancy Hamilton, owners of Inslaw Inc., and reportedly modified for international espionage. As always, should you or any of your associates be caught, the governments of Canada and the United States will disavow any knowledge of your actions. This recording will self-destruct in five seconds. Good luck, Sean.”

Sounds like the opening taped message from an episode of the 1960s TV action series Mission Impossible. But just such a mission was offered – and accepted – by two investigators of the National Security Section of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). The Mounties then covertly entered the United States in February of last year and for nearly eight months conducted a secret investigation into the theft of the PROMIS software and whether and by whom it had been obtained for backdoor spying. PROMIS is a universal bridge to the forest of computer systems. It allows covert and undetectable surveillance, and it and its related successors are unimaginably important in the new age of communications warfare.

In this exclusive investigative series Insight tracks the Mounties and explores the mysteries pursued by the RCMP, including allegations involving a gang of characters believed to be associated with the suspected theft of PROMIS, swarms of spies (or the “spookloop” as the Mounties called them), the Mafia, big-time money laundering, murder, international arms smuggling and illegal drugs – to name but a few aspects of the still-secret RCMP probe.

But the keystone to this RCMP investigation is PROMIS, that universal bridge and monitoring system, which stands for Prosecutor’s Management Information System – a breakthrough computer software program originally developed in the early 1970s by the Hamiltons for case management by U.S. prosecutors. The first version of PROMIS was owned by the government since the development money was provided by the Department of Justice (DOJ), but something went awry on the way to proprietary development.

For more than 15 years the story of the allegedly pirated Hamilton software, and how it may have wound up in the hands of the spy agencies of the world, has been hotly pursued by law-enforcement agencies, private detectives, journalists, congressional investigators, U.S. Customs and assorted U.S. attorneys. Even independent researchers have taken on the role of counterespionage agents in a quest to uncover the truth about this allegedly ongoing penetration of security.

But each new U.S. investigation has failed fully to determine what happened. While the Mounties encountered a similar fate, officers Sean McDade and Randy Buffam have been the most successful to date. Last May, with the assistance of Hercules, Calif., detective Sue Todd, the Mounties walked away with a package of startling evidence that many believe will solve the case of the pirated software and its reported continuing use for international espionage and a host of other illegal activities.

Insight has spent months retracing the steps of the two RCMP officers and interviewing their sources, poring over copies of documents they secured, listening to tape recordings of meetings in which they were involved and reviewing scores of reports and depositions that have been locked up for years.

The result is this first installment of a four-part investigative report about how the Mounties conducted their covert border crossings and investigation that ranged across the United States and back again before returning to Canada where they discovered their cover had been blown. By late summer of 2000 the Canadian press was reporting not only the existence of this secret national-security probe – “Project Abbreviation” – but that if the reported allegations prove true “it would be the biggest-ever breach of Canada’s national security.” Confusing official comments about the probe added further mystery. But Insight has confirmed many of the details, including the fact that the investigation is continuing. And it’s serious stuff.

McDade began his extended trip into international espionage early last year. It began at least on Jan. 19, 2000, with an e-mail that said: “I am looking to contact Carol (Cheri) regarding a matter that has surfaced in the past. If this e-mail account is still active, please reply and I will in turn forward a Canadian phone number and explain my position and reason for request.” This communication, from e-mail account simorp (PROMIS spelled backward), was the first of hundreds sent during an eight-month period from “dear hunter,” also known as Sean McDade. It reached Cheri Seymour, a Southern California journalist, private detective and author of a well-regarded book, Committee of the States.

Seymour became one of the most important of McDade’s contacts during the Mounties’ continuing investigation. Although she had agreed to remain silent about their probe until McDade filed a report with his superiors, she changed her mind when news of the probe began to leak in the Canadian press. It was then that the Southern Californian contacted Insight and offered to share what she knew about the investigation if this magazine would look into the story. And what a story it is.

A petite, attractive, unassuming middle-aged woman, Seymour looks more like a violinist in a symphony orchestra than an international sleuth. But one quickly becomes aware of the depth of her knowledge not only of the alleged theft of the PROMIS software, but also of other reported illegal activities and dangerous characters associated with it.

Seymour’s involvement with PROMIS began more than a decade ago while working as an investigative reporter on an unrelated story about high-level corruption within the sheriff’s department of the Central California town of Mariposa, near Yosemite National Park, where deputies reportedly were involved in illegal-drug activity. The dozen or so who were not involved repeatedly had begged the journalist to conduct an investigation. When she learned that one of the officers had taken the complaints to the state attorney general in Sacramento and within weeks was reported missing in an alleged boating accident on nearby Lake McClure, she launched her probe.

The owner of the local newspaper, the Mariposa Guide, in time contacted ABC television producer Don Thrasher and the story of the corruption within the Mariposa Sheriff’s Department ran in 1991 on ABC’s prime-time television news program 20/20. Seymour’s investigation is chronicled in a draft manuscript called the “Last Circle,” written under her pseudonym Carol Marshall but made available anonymously on the Internet in 1997. PROMIS then was only a sidebar to the larger story, but it was this obscure Internet posting that led RCMP investigators McDade and Buffam to Seymour’s living room two years later.

According to Seymour: “Nothing [previously] came of the work I did. Even though in October of 1992 I had sent a synopsis of my work to John Cohen, lead investigator on the House Judiciary Committee, looking into the theft of PROMIS and its possible connections to the savage death of free-lance journalist Danny Casolaro. But by then the committee had completed its report and published its findings. It was a closed case. Nothing ever happened with the connections I was able to make among the players involved in the theft of PROMIS and illegal drug trafficking and money laundering.” That is, until McDade sent his first cryptic e-mail.

Within a week the Mountie had arranged to meet Seymour at her home to discuss aspects of his own secret investigation and begin the laborious task of copying thousands of documents Seymour had collected from an abandoned trailer in Death Valley belonging to a man at or near the center of the PROMIS controversy, Michael Riconosciuto, a boy genius, entrepreneur, convicted felon – and the man who has claimed that he modified the pirated PROMIS software. The documents provided specific information about Riconosciuto’s connections to the Cabazon Indian Reservation, where he claims to have carried out the modification, but they also painted a clear picture of the men with whom Riconosciuto associated, including mob figures, high-level government officials, intelligence and law-enforcement officers and informants – even convicted murderers.

Before McDade focused on a three-day copying frenzy, the Mountie gathered Todd, Seymour and an impartial observer invited by Seymour to corroborate the meeting around Seymour’s dining-room table and began to tell a dramatic tale of government lies and international espionage.

“I sat there with my mouth wide open and my eyes practically popping out of my head – you know, that deer-in-the-headlights look,” Seymour recounts. “I couldn’t believe what this guy was telling us. It wasn’t anything I anticipated or even was prepared to hear.” She says, “McDade told us his investigation had to do with locating information on the possible sale of PROMIS software to the RCMP in the mid-1980s. He had found evidence in RCMP files that PROMIS may have been installed in the Canadian computer systems, and he said an investigation was initiated by his superiors at the RCMP.”

According to Seymour, “McDade said that the details of his findings in Canada could conceivably cause a major scandal in both Canada and the United States.i He said if his investigation is successful it could cause the entire Republican Party to be dismantled – that it would cease to exist in the U.S.” Hyperbole, perhaps, but bizarre stuff from a professional lawman.

“Then,” continues Seymour, “he said something that was just really out there. He stood in my dining room with a straight face and told us that … more than one presidential administration will be exposed for their knowledge of the PROMIS software transactions. He said that high-ranking Canadian government officials may have unlawfully purchased the PROMIS software from high-ranking U.S. government officials in the Reagan/Bush administration, and he further stated that the RCMP has located numerous banks around the world that have been used by these U.S. officials to launder the money from the sale of the PROMIS software.” Seymour was stunned. “First,” she says, “I wondered if this guy was for real and, second, did he have something against Republicans.” Just when she thought things couldn’t get any weirder, “McDade detailed a December 1999 meeting at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico attended by the heads of the intelligence divisions of the U.S. [CIA], Great Britain [MI6], Israel [Mossad] and Canada [CSIS]. McDade said the topic of the discussion was UNIQUE ELEMENTS, and that during this meeting it allegedly was revealed that all four allied nations share computer systems and have for years. The meeting was called after a glitch was found in a British computer system that had caused the loss of historical case data.”

McDade continued with this scenario by telling the astonished group: “The Israeli Mossad may have modified the original PROMIS modification [the first back door] so it became a two-way back door, allowing the Israelis access to top U.S. weapons secrets at Los Alamos and other classified installations. The Israelis may now possess all the nuclear secrets of the United States.” According to Seymour, he concluded by saying that “the Jonathan Pollard [spy] case is insignificant by comparison to the current crisis.”

This was pretty heavy stuff for a foreign law-enforcement agent to be bandying with complete strangers. And it made those present uncomfortable. Was McDade making up wild tales for some as yet unrevealed purpose or was he, in fact, reporting what he knew to be true based on information he had gleaned from his investigation?

Insight has tried repeatedly to contact McDade and his superiors to discuss the Mountie’s accounts of espionage and other crimes only to be rebuffed through official channels. But in carefully assembling and independently checking disparate pieces of the McDade story line Insight was able to confirm that there was indeed a December 1999 meeting at the Los Alamos National Laboratory and the topic of the meeting was, indeed, code-named UNIQUE ELEMENTS.

Seymour never learned further details about that meeting, though she tried, alerting several U.S. senators, including Charles Robb, D-Va., Jeff Bingaman, D-N.M., and Richard Bryan, D-Nev., about what McDade had told her in February – nearly four months before the public was made aware of massive computer problems at Los Alamos (see “DOE `Green Book’ Secrets Exposed,” Jan. 1). Ironically, Congress was probing such lapses, but only Bob Simon, Bingaman’s staff director on the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, responded. Simon advised that he would show the letter to the senator and possibly refer “some or all of the information in the letter to Ed Curran, director of the Department of Energy’s [DOE] Office of Counterintelligence.”

Seymour never had any further communication from Bingaman’s office, the DOE or any federal investigator seeking to discover which “foreign agent” had told her of severe computer leakage from Los Alamos long before it became public knowledge.

How McDade knew what he claimed may never be made public. But what is known can be pieced together from the many contacts he had with individuals having historical knowledge of the allegations surrounding PROMIS and a host of other seemingly unrelated criminal enterprises and crimes.

For instance, in January 2000 McDade contacted PROMIS developers and owners Bill and Nancy Hamilton, explaining what his investigation was about; what, to date, had surfaced; and what the implications might be. “McDade said my government made two untruthful statements in 1991 [the year congressional hearings were held on the theft of PROMIS],” Bill Hamilton tells Insight. “The first was that they [Canada] had developed the software in-house. McDade said that wasn’t true, it just materialized one day out of nowhere. The second untruth was that they [the Canadian government] had investigated this. McDade said that his investigation was the first.”

Hamilton further explained that “McDade believed PROMIS software was being used to compromise their [Canada’s] national security.” Needless to say, this was interesting news to Hamilton, given that it was “the second time the Canadian government has said they have our software, only to retract the admission later.” The first time was in 1991, he recalls. “They contacted us to see if we had a French-language version because they said they only had the English version – which, by the way, we did not sell to them. At first we didn’t take it seriously because it was before we were aware that the software was reportedly being used in intelligence. We just knew that the U.S. Department of Justice acted rather strangely, took our software and stiffed us. It never occurred to us that the software was being distributed to foreign governments,” Hamilton tells Insight.

“When they [Canada] followed up their call with a letter saying PROMIS software is used in a number of their departments – 900 locations in the RCMP, to be exact – Nancy and I said `Hey, wait a minute.'”

Of course, laughs Hamilton, “when one of our newspapers in the U.S. got hold of that information and printed it, the Canadians retracted and apologized for a mistake. They now said the RCMP never had the software.”

It is important to note that the alleged theft of PROMIS software was well investigated. However, no investigation by any governmental body, including the U.S. House Judiciary Committee, which made public its findings in September 1992, the Report of Special Counsel Nicholas J. Bua to the Attorney General of the United States Regarding the Allegations of Inslaw, Inc., completed in March 1993, nor the Justice Department’s Review of the Bua Report, which was published in September 1993, confirmed that any agency or entity of Canada had obtained and used an illegal copy of the Hamiltons’ PROMIS software.

A Justice report commissioned by Attorney General Janet Reno concluded the same but did confirm that a system called PROMIS was being used by Canadian agencies but claimed that this system was totally different – it was just a coincidence that the two software programs had the same unusual name and spelling.

So what happened over the course of 10 years to lead the RCMP’s top national-security investigators to probe the matter anew and to do so with such secrecy throughout the United States and Canada? Why would McDade, by all accounts a seasoned and well-respected Mountie, tell whopping tales to so many people, including not only Bill Hamilton but strangers Seymour, Todd and others?

The answers may be found in the pattern of people who were questioned by the Mounties. The information for which they were asked and which they reportedly provided, may reveal that the alleged theft of the breakthrough PROMIS software was not, in fact, the focus of the investigation, but was secondary to how the software has come to be used.

In August 2000, McDade told the Toronto Star’s Valerie Lawton and Allan Thompson, “There are issues that I am not able to talk about and have nothing to do with what you’re probably making inquiries about,” which centered on PROMIS. Was the Mountie revealing that his investigation had reached the level he had unguardedly revealed to Seymour and friends?

Surprisingly, McDade did not focus his investigation on interviews with government officials who were involved with the PROMIS software. Rather he focused on people who claimed to have knowledge of the purported theft, many of whom also have been connected to other illegal activities, including drug trafficking and money laundering. And Michael Riconosciuto was at the top of McDade’s list.

With the help of Detective Todd, who had facilitated the Mounties’ meetings with the hope of also obtaining information about the 1997 execution-style double homicide of Neil Abernathy and his 12-year-old son, Benden, McDade was given access to Riconosciuto and people and information that even few law-enforcement officers in the United States have secured. In fact, the assistance the Mountie received secretly from U.S. authorities was stunning and included access to information from highly confidential FBI internal files and case jackets (including the names of confidential witnesses and wiretapping information), U.S. Bureau of Prisons files, local law-enforcement reports and reportedly even classified U.S. intelligence data.

It was with this kind of help that McDade was able to walk away with what many believe to be key material evidence in the PROMIS software legal case – material evidence of which only Riconosciuto had knowledge. After extensive interviews with Riconosciuto in a federal penitentiary in Florida, McDade in May 2000 made a $1,500 payment on a defaulted storage unit in Vallejo, Calif., that belonged to Riconosciuto. Poring through floor-to-ceiling boxes, McDade hit pay dirt when he found six RL02 magnetic tapes that Riconosciuto said were the PROMIS modification updates – the boot-up system for PROMIS he claimed to have created.

Coupling those storage-unit files with the thousands of pages of documents Seymour had obtained some years earlier from an abandoned trailer Riconosciuto had rented in the desert, McDade walked away with the whole kit and caboodle without so much as a peep out of U.S. law-enforcement or intelligence agencies. At least until now.

Today, that evidence is in the hands of foreign agents – our neighbors up north in Canada. When questioned about the magnetic tapes, the RCMP would neither confirm nor deny that they were in its possession. Michele Gaudet, the RCMP spokesman, did tell Insight that the investigation is ongoing and it is very much about the PROMIS software – software that may or may not involve back-door entrance into the most secret computer systems in the Western world.

****OVERVIEW OF INSIGHT’S FOUR-PART SERIES****

This four-part series is about how a foreign law-enforcement agency, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), covertly entered the United States and for nearly eight months conducted a secret investigation about the alleged theft of PROMIS software and the part it may play in suspected security breaches in Canada, the United States and other nations.

In Part 1, Insight tracks the early movements of two RCMP national-security officers – Sean McDade and Randy Buffam – to contacts throughout the United States, including private detective Cheri Seymour, an author and former investigative journalist. Seymour has spent years investigating the alleged theft of PROMIS and illegal activities reportedly associated with it. McDade outlined the nature of his investigation and what is at stake. He described potential security breaches in his country and detailed top-level secret meetings at U.S. national laboratories about similar security problems in the United States. Here, readers also will learn how with the help of a small-town California detective, Sue Todd, the Mounties managed to leave the United States with material evidence that may be crucial to solving a major espionage puzzle.

In Part 2, Insight follows the Mounties to the California desert in search of confirmation of allegations made by Michael Riconosciuto, the boy genius who reportedly modified the stolen PROMIS software for international espionage while working as research director of an alleged Cabazon/Wackenhut Joint Venture on the Cabazon Indian Reservation in Indio, Calif. It also is at Cabazon that other “characters” reportedly involved in the theft of the software were revealed and Riconosciuto’s connections to them confirmed. It is a strange mix of alleged players – the Wackenhut Corp., government officials, mob-related goodfellows and murderers. Insight also will look at claimed arms deals and government research at the Cabazon reservation, including a secret weapons demonstration in Indio attended by many of the same cast reportedly key to the theft of PROMIS.

In Part 3, readers will watch as the Mounties begin a lengthy review of a U.S. government official, Peter Videnieks, the Justice Department employee overseeing the PROMIS contract, who allegedly made the theft of the software possible. The U.S. Customs Service began an investigation of Videnieks based on its suspicion that he committed perjury when he testified at a 1991 trial of Riconosciuto. Based on documents obtained from federal law-enforcement agencies, Insight looks at a U.S. Customs Service investigation of Videnieks, which ultimately was dropped. The Mounties also probed a Customs investigation of reported drug trafficking and technology transfers over the Maine/Canadian border.

In Part 4, Insight will review the numerous investigations conducted by law enforcement, beginning with the Mounties, concerning the alleged theft of the PROMIS software and individuals reportedly associated with that theft. Readers will see how each investigation began with review of the “theft” but quickly led into other suspected illegal activities, including technology transfers. This last part also will review how each new investigation has overlooked key evidence and seen careers threatened.

By Paul M. Rodriguez

The Plot Thickens in PROMIS Affair

Feb 5, 2001

By Kelly Patricia O Meara

Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) officers Sean McDade and Randy Buffam set out in January 2000 on an eight-month secret investigation in the United States. The two were attempting to determine whether Canada’s law-enforcement and intelligence agencies were using an allegedly pirated software program called PROMIS that had been modified to be monitorable by shadowy interests said to have the electronic key; and, if so, whether Canada’s national security had been compromised because of the suspected electronic backdoors installed in the software.

Much of the Mounties’ investigation focused on the reported activities and relationships of Michael Riconosciuto, a computer wizard who claimed to have modified the PROMIS software for illegal use. A convicted felon, Riconosciuto also claimed knowledge of a compendium of suspicious characters and activities that include:

* Arms development for an alleged joint venture between the Cabazon Indians of Indio, Calif., and the Wackenhut Corp.;

* A former high-ranking Justice Department attorney named Mike Abbell and his alleged relationship with the Cali drug cartel; and

* Riconosciuto’s own activity as an undercover operative in a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) sting operation in Lebanon.

Insight has followed the trail of the two RCMP investigators as they moved secretly throughout the United States collecting hard data from a variety of sources and interviewing witnesses, including Riconosciuto. They ultimately returned to Canada to continue their still-secret national-security probe that raises troubling questions about international espionage, crime and scandalous cover-ups said to date back more than a decade.

In this second installment of an exclusive four-part series, Insight focuses on Riconosciuto, on whom the RCMP investigators invested so much time, expense and effort to examine and try to confirm his shocking stories. By following the Mounties, Insight has assembled new information that sheds light on the shadowy world in which Riconosciuto operated and what the RCMP found – including long-sought computer tapes that Riconosciuto has said contain a version of PROMIS that was stolen by high-level U.S. government officials and that he then modified for illegal purposes.

This was not the first time such claims had been made. Before the RCMP got involved, a great deal of this information was provided to Congress (among others) and surfaced during a 1992 taped telephone conversation between Riconosciuto and an FBI agent at a time Riconosciuto was on trial for the manufacture and sale of methamphetamine and was attempting to trade information to the FBI in exchange for entry to the federal Witness Protection Program.

But, as so often with Riconosciuto, the stories he offered to federal agents were not confirmed or just ignored. That is, until the RCMP entered the picture last year and got a break. Helping the Mounties was Cheri Seymour, a Southern California journalist turned private detective. Years before, in January 1992, she had retrieved boxes of documents from Riconosciuto’s hidden desert trailer. The Mounties spent three days copying these documents and, with the help of Seymour, returned to the trailer where yet more documents were retrieved.

These combined Riconosciuto papers revealed the dark and disturbing landscape of crime, espionage and betrayal of which he had been part – one that ever since his arrest and conviction in 1992 had been labeled the fictional embellishments of a convicted felon.

Each new twist and turn of the covert investigation took the Mounties deeper into a forest of bizarre machinations as they sought to validate information which, though it had no direct connection to the alleged theft of the PROMIS software, raised astonishing questions about national security and organized crime. This is not to say the RCMP agents didn’t probe the allegations that Canada’s law-enforcement and intelligence services were operating a stolen version of the software developed years before by Bill and Nancy Hamilton.

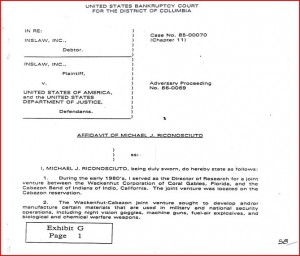

The Hamiltons own a company called Inslaw, and it is they who, in the early 1970s, developed a version of PROMIS for the Justice Department. At some point, they have claimed, a proprietary version of their software was stolen and a dispute arose with the government. In March 1991, just before Riconosciuto was arrested on illegal drug charges, he provided a sworn affidavit to Inslaw stating that between 1981 and 1983 he had made modifications to a pirated version of PROMIS. He told Inslaw, and subsequently Congress and federal investigators, that he did so when he was director of research for a joint venture between the Cabazon Indians and the Wackenhut Corp.

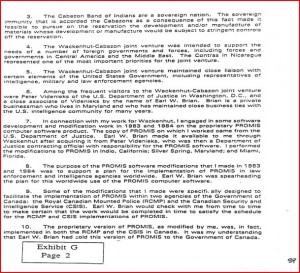

At the time, there were fewer than two dozen members of the Cabazon Band of Mission Indians. John Nichols, who is not an American Indian, was the administrator of the tribe’s business affairs, which included the joint-venture partnership with Wackenhut, one of the top private security agencies in the world, run by former FBI and other intelligence specialists.

The Indian reservation presented unique opportunities for secrecy, according to interviews and documents obtained by Insight. Under broad state and federal exemptions, Indian reservations enjoy status just short of being sovereign nations and are free to govern within the confines of the reservation without outside intervention. Wackenhut was one of the first corporations to take advantage of this special status.

Whether the Cabazon/Wackenhut “joint venture” existed is not in question. What have been dismissed by federal investigators are Riconosciuto’s claims about what went on at the reservation and the people involved.

For example, Riconosciuto has maintained that one of the projects he was involved in dealt with new munitions he and the Cabazon/Wackenhut partnership had created, not to mention a nifty new night-vision device. RCMP officers McDade and Buffam obtained a copy of a 1991 “Special Operations Report” (SOP) that was written by Gene Gilbert, an investigator for the district attorney’s office in Riverside, Calif. In this report – a copy of which was given to the House Judiciary Committee in 1991 and subsequently to the Justice Department in 1993 – Gilbert describes a weapons demonstration that took place in September 1981 at the Lake Cahuilla Shooting Range in Indio, Calif. Details of who attended this test nearly 20 years ago, Riconosciuto claims, should corroborate his assertions about people he associated with involved in the alleged theft of the PROMIS software and other activities in which the RCMP officers now are probing.

U.S. federal investigators dismissed the report because, they said, the document was a re-creation of 10-year-old events based on recollections Gilbert had cobbled together at the request of federal authorities. The RCMP officers traveled to Riverside in August 2000 to see for themselves. According to a law-enforcement officer who asked not to be identified, Gilbert not only verified the information in his 1991 SOP report but allowed the Mounties to review all the contemporaneous backup in local police-department files associated with the weapons demonstration and other activities at the reservation.

Insight has obtained some of these crucial 1980s police-intelligence files which Gilbert used for his 1991 SOP report. And these confirm that there was a demonstration in 1981 consisting of tests for a new night-vision device and a firing of special semiautomatic weapons. The records show it was attended by Riconosciuto and 15 others – including two anticommunist Nicaraguan freedom fighters identified as Eden Pastora Gomez (code-named “Commander Zero”) and Jose Curdel (“Commander Alpha”); John Vanderworker, a former CIA employee; Wayne Reeder, a wealthy California developer and investor in the Cabazon Reservation; Peter Zokosky, a board member of Meridian International Logistics who also was a Cabazon investor and former owner of Armtec Defense Products Inc.; and John Philip Nichols, administrator of Cabazon, to name a few.

This is not the only story that emerged as the RCMP investigated Riconosciuto’s revelations. For instance, for years he had said he’d worked for the government, briefing and lecturing military brass and Pentagon officials. In a January 1992 letter obtained by Insight on Wackenhut stationery, the company’s director of corporate relations, Patrick Cannan, writes that “John P. Nichols had first introduced Riconosciuto to Wackenhut (Frye, V.P. of Wackenhut, Indio, Ca., office) on a May 1981 trip to the U.S. Army installation at Dover, N.J., where Nichols, Zokosky, Frye and Riconosciuto met with Dr. Harry Fair and several of his Army associates who were the project engineers on the Railgun Project. Riconosciuto and these Army personnel conducted an extensive and highly technical `theoretical’ blackboard exercise on the Railgun and, afterward, Dr. Fair commented that he was extremely impressed with Riconosciuto’s scientific and technical knowledge in this matter.” The letter goes on to state that Dr. Fair considered Riconosciuto a “potential national resource.”

The significance of this is that it is consistent with evidence unearthed by RCMP investigators that Riconosciuto’s claims of technical and scientific expertise and access are not rantings.

The RCMP investigators also discovered another link in a Riconosciuto story that had been dismissed. The permit to hold the arms demonstration in 1981 at Lake Cahuilla was obtained by Meridian Arms, a subsidiary of Meridian International Logistics, owned by Robert Booth Nichols, a self-proclaimed CIA operative and licensed arms dealer (and no relation to Cabazon administrator John Nichols). Riconosciuto for years was a partner with Booth Nichols in the Meridian Arms business and, at the time the permits were approved for the Lake Cahuilla weapons demonstration, Nichols was unaware that he was being investigated by the FBI for suspected mob-related money laundering of drug profits and for stock fraud.

Booth Nichols also served on the board of First Intercontinental Development Corp. (FIDCO), a building/construction company. Among Nichols’ corporate partners at FIDCO in the 1980s were Michael McManus, then an aide to President Reagan; Robert Maheu, former chief executive officer of Howard Hughes Enterprises; and Clint Murchison Jr. of the Murchison empire based in Dallas.

Riconosciuto long has maintained that Booth Nichols and FIDCO were associated with U.S. intelligence agencies and used as a cutout. Again, whereas others summarily had dismissed this claim, the RCMP investigators pursued the lead, poring over documents from the long-abandoned Riconosciuto storage and in the files of U.S. law-enforcement agencies. For example, RCMP obtained FBI wiretap summaries of telephone conversations between Nichols and another of his then-partners in FIDCO, Eugene Giaquinto, who at the same time also was president of MCA Home Entertainment Division. The wiretap summaries reads like a who’s who of alleged mob figures with close ties to the motion-picture industry. The Mounties also received substantial related information from classified internal FBI files.

But, based on Insight’s own sources, what the RCMP investigators were after wasn’t just PROMIS but people associated with Riconosciuto and their business ties in a vast array of enterprises that include intelligence activities overseas. Somehow, this network was tied in to what the Mounties were investigating involving security lapses such as those at the Los Alamos National Laboratory last year that McDade and Buffam knew about – and shared with Seymour and others – months before the news hit U.S. newspapers. And it appeared that Riconosciuto and his cronies were in the thick of such international intrigue – especially Booth Nichols.

In response to RCMP requests to help to corroborate Riconosciuto’s claims and connections to Booth Nichols, Seymour provided McDade a January 1992 recording of a telephone conversation between Riconosciuto and an FBI agent. From this tape McDade heard Riconosciuto claim that Booth Nichols was connected to a high-ranking Justice Department official. Riconosciuto also tells the FBI agent that “the bottom line here is Bob [Nichols], Gilberto Rodriguez, Michael Abbell [who’s now an attorney in Washington but then was with the Criminal Section of the Justice Department], Harold Okimoto, Jose Londono and Glen Shockley are all in bed together.”

Riconosciuto also details in the tape-recorded phone call specific information about an alleged meeting between Booth Nichols and Abbell. He subsequently provided the FBI agent a handwritten note with additional information about the alleged Abbell meeting: “Bob [Nichols] handed him [Abbell] $50,000 cash to handle an internal-affairs investigation the Department of Justice was having that would lead to extradition of [brothers] Gilberto and Miguel Rodriguez and Jose Londono. Bob said it was necessary to `crowbar’ the investigation because they were `intelligence’ people.”

What is significant, and of interest to the Mounties, is that Riconosciuto fingered Abbell’s ties to the Cali drug cartel three years before Abbell was indicted in Miami on federal criminal charges that the former official did work on behalf of the Cali cartel and its leaders. (Abbell was convicted of money laundering in July 1998 and sentenced to seven years in prison.) Interestingly enough, once McDade returned to Canada with tapes of a dozen telephone conversations and his secret investigation began to leak in the Canadian press (albeit briefly), he mailed to Seymour a transcript of the Riconosciuto taped conversation with the FBI agent. Was this a message?

The Mounties clearly were interested in Riconosciuto’s partner of nearly 20 years, Booth Nichols. This connection was strange, according to those interviewed by Insight, because Booth Nichols apparently had nothing to do with PROMIS and everything to do with other more nefarious allegations. And the Mounties also were interested in claims Riconosciuto has made about his participation in a DEA drug-sting operation in Cyprus.

In one of the taped interviews Riconosciuto had with the FBI agent, he says that he was in Lebanon working on “communications protocol” for FIDCO in the Middle East to rebuild the infrastructure of two cities in Lebanon. Why the RCMP would be interested in this additional twist in the intrigue is unknown, but Insight has obtained documents that support the convicted felon’s claims here as well. A June 1983 letter from Michael McManus Jr., the Reagan assistant who also sat on the FIDCO board, to George Pender, president of FIDCO, describes the administration’s support for the rebuilding of Lebanon: “Without question FIDCO seems to have a considerable role to offer, particularly in the massive financial participation being made available to the government of Lebanon.”

There also is a July 1983 letter to the president of Lebanon, Amin Gemayel, from Pender in which FIDCO’s desire to participate in the rebuilding of Lebanon is discussed. What is interesting about this letter is that Pender advises the Lebanese president that he (Pender) “may be reached via telex 652483 RBN Assocs. LSA.” And whose address is that? None other than Booth Nichols. The same Nichols who at the time was a board member of FIDCO and under investigation by the FBI for suspected drug trafficking, money laundering and connections to the mob – and the same man who obtained the permits at the Cahuilla gun range for the weapons demonstration to Nicaraguan Contra leaders and others.

The more the Mounties dug, the weirder the connections got and the more the convicted felon’s stories of the bizarre underground seemed to be borne out. Besides its interest in the RCMP probe and what it was uncovering, Insight also sought – and confirmed – the details of many other Riconosciuto accounts of these intrigues.

Riconosciuto has said he was involved in that DEA drug-sting operation in the Middle East while he was working on communications protocol for FIDCO. What part he played in any alleged sting operation is unknown but, based on what Riconosciuto told the FBI agent in those taped conversations, detailed information about a safe house used by the DEA in Cyprus seems accurate. According to Riconosciuto, the DEA safe house was located in Nicosia, Cyprus, and operated under the code name of Eurame Trading Ltd., which was located on Collumbra Street. “It was an apartment and it had a ham-radio station. It was ICOM,” Riconosciuto said, “a single side-band amateur radio setup. It [the apartment] was on the top floor.” There is corroboration for these details.

Lester Coleman, a former contract employee with the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) who was on loan to the DEA in the late 1980s, wrote a book in 1993 called Trail of the Octopus: From Beirut to Lockerbie, Inside the DIA. Coleman claims there to have worked out of a safe house in Cyprus at the same location Riconosciuto described and under the same name, Eurame Trading Ltd. Coleman also confirmed secret Beka Valley drug shipments and the names of the U.S. agents working undercover in Cyprus that Riconosciuto had revealed to the FBI in 1992 – a year before it was outlined in Coleman’s book.

Insight asked Coleman who would know about such a secret U.S. government safe house, let alone a cutout company? “I don’t know,” Coleman says, “unless he was there. i I have never met or talked with [Riconosciuto], so I have no idea whether he was there or not. i But what he is describing is accurate. No one would know about the ICOM radio unless they had been there and seen it,” Coleman says.

Again, like Riconosciuto’s comments about Justice Department attorney Abbell and his connections to the Cali drug cartel, Riconosciuto knew detailed information well before the public. And he tried to tell the FBI, among others, but to no avail. The stories then seemed too wild and woolly to be credible.

But they were credible to these RCMP investigators, who spent considerable time, effort and money to prove or disprove what Riconosciuto has been saying. So clearly did this key source for their original inquiry into the alleged theft and misuse of the PROMIS software lead the RCMP afield that one must wonder why. Is it possible that the Canadian investigators focused so much interest on these associates and tales by Riconosciuto to test his credibility about allied espionage matters and PROMIS?

No one is talking about what the RCMP probe ultimately was after or what was taken back to Canada, let alone McDade. However, according to RCMP spokesman Michelle Gaudet, this investigation is “ongoing within the national-security perspective.”

To be continued next week.

Feb 12, 2001

By Kelly Patricia O’Meara

During an eight-month secret investigation in the United States last year by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), two of its top national-security investigators focused their probe on a former high-ranking Justice Department official alleged to have been involved in the theft of the PROMIS computer program. Subsequent modifications of this software are believed to have yielded secret backdoor access allowing widespread computer espionage.

In this, the third of a four-part exclusive series, Insight continues to follow Mounties Sean McDade and Randy Buffam as they pursue allegations that Canada’s intelligence and law-enforcement agencies have been operating the stolen version of PROMIS and that their most secret computer systems have, as a result, been compromised.

Much of the investigation centered on two men – Michael Riconosciuto and Peter Videnieks. The former is a convicted felon who has claimed that he modified a stolen version of the Inslaw-developed PROMIS. The latter is the man fingered by Riconosciuto as a high-ranking Department of Justice official involved in the theft of the software.

In Part II of this series (see “The Plot Thickens in PROMIS Affair,” Feb. 5), Insight took an in-depth look at Riconosciuto and allegations he has made involving PROMIS and other national and international intrigue, including development of a new line of guns and night-vision goggles and a joint venture between a little-known band of American Indians called the Cabazons and the Wackenhut Corp., an international security firm. Other trails led to government-sanctioned drug deals and claims that another former Justice lawyer was involved with the Cali drug cartel.

Riconosciuto’s stories had been dismissed by federal investigators, but the RCMP unearthed evidence that gave them credibility. What’s more, Insight confirmed that Riconosciuto had provided just such startlingly detailed information to an FBI agent well before it had become publicly known.

For the Mounties, whose still-secret investigation continues, each layer they peeled back on Riconosciuto’s stories revealed a path to yet more information that might confirm their country’s worst fears: that key government computer systems were using stolen software that had been modified to allow complete access for espionage.

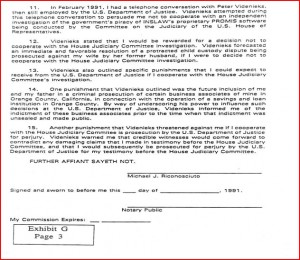

In a 1991 affidavit to William and Nancy Hamilton, the owners of Inslaw who had developed PROMIS, Riconosciuto not only swore that he put the backdoors into a stolen version of the software but also claimed that Videnieks, the Department of Justice official who in the early 1980s oversaw the PROMIS-software contract, participated in the alleged scheme along with a man named Earl W. Brian. Both men, Riconosciuto swore under penalty of perjury, visited him often at the Cabazon/Wackenhut facilities.

As with other Riconosciuto stories, the Mounties looked for confirmation and focused intensely on a U.S. Customs Service internal investigation of Videnieks, a contract specialist who was on loan from Customs. Customs conducted a two-and-a-half-year probe of Videnieks because of suspicion he had committed perjury in 1992 while giving testimony in the trial of Riconosciuto, who had been arrested for drug offenses. In an attempt to enter the federal witness-protection program, Riconosciuto told federal investigators that he was set up on phony charges because of the affidavit he gave the Hamiltons.

Videnieks has denied any knowledge of such schemes, the first time in sworn testimony during the Riconosciuto trial in Tacoma, Wash., in January 1992. Asked if he knew either Riconosciuto or Brian, and if he ever had been to the Wackenhut/Cabazon joint venture or heard of it, Videnieks responded, “No, I don’t. i No, I don’t. i No, I haven’t.” Customs soon thereafter launched a far-reaching internal-affairs investigation of Videnieks.

However, it is allegations of government interference in the Videnieks case and contradictory conclusions about the basic facts in the legal saga surrounding the Hamiltons’ allegations of official wrongdoing that the Mounties seem intent on clearing up. For instance, in a January 1988 decision by U.S. Bankruptcy Court Judge George Bason (Inslaw, Inc. v. United States of America and the United States Department of Justice), the jurist concluded that Justice Department and unnamed U.S. government officials “engaged in an outrageous, deceitful, fraudulent game of `cat and mouse,’ demonstrating contempt for both the law and any principle of fair dealing.” These harsh words came at the end of a long trial in which Inslaw had filed for bankruptcy as a result of not being paid for its PROMIS-related work for Justice. This work was, in essence, to establish a computer-software system that could track the status of cases in all U.S. attorneys’ offices and federal courts.

Justice appealed Bason’s ruling and, in November 1989, U.S. District Court Judge William Bryant found in favor of Inslaw, stating: “It is not necessary to duplicate the bankruptcy court’s exhaustive findings of fact here. i There is convincing, perhaps compelling, support for the findings set forth by the bankruptcy court i [that] the government acted willfully and fraudulently to obtain property that it was not entitled to under the contract.”

End of dispute, right? Wrong. For the Hamiltons the case has yet to be resolved since they have not been paid.

While the Inslaw case wound its way through the courts, Congress also got into the act in the late 1980s as the House Judiciary Committee launched a far-reaching probe of its own. And in September 1992 it issued a report that forcefully stated that “there appears to be strong evidence, as indicated by the findings in two federal-court proceedings as well as by the committee investigation, that the Department of Justice acted willfully and fraudulently and took, converted and stole Inslaw’s ENHANCED PROMIS by trickery, fraud and deceit.” The reference to “ENHANCED PROMIS” was to a proprietary version the Hamiltons had developed that they alleged later was stolen by the government.

The result of the Judiciary Committee report was that in 1993 Attorney General William Barr appointed Nicholas J. Bua to investigate and prepare a report on the Inslaw matter. The results of this investigation, the Report of Special Counsel Nicholas J. Bua to the Attorney General of the United States Regarding the Allegations of Inslaw Inc., found: “There is no credible evidence to support the allegation that members of DOJ conspired with Earl Brian to obtain or distribute PROMIS software. There is woefully insufficient evidence to support the allegation that DOJ obtained an enhanced version of PROMIS through `fraud, trickery, and deceit’ or that DOJ wrongfully distributed PROMIS within or outside of DOJ.”

And still another Justice probe, launched by Attorney General Janet Reno when she took office, concluded in September 1994 that the Bua report was correct – there was nothing to the now-convoluted charges that PROMIS was stolen and sold illegally or that the Hamiltons were due any monies. Moreover, the Reno report concluded that Riconosciuto’s stories were not confirmable and that Videnieks was not involved in the alleged schemes laid out by the convicted felon.

Canada also conducted a probe in the early 1990s and concluded that allegations concerning its use of a stolen version of PROMIS were lies. The Reno report affirmed Canada’s conclusions as well.

So it was with great surprise that Insight learned last year about the secret RCMP investigation. McDade and Buffam were on the trail of PROMIS anew and were reviewing all the machinations that have accompanied this exotic story for more than a decade.

It is unclear what sparked the Mounties’ probe except that it involves Canada’s national security. And of keen interest to the RCMP investigators were Riconosciuto and Videnieks, two men concerning whom the Mounties spent considerable time, money and effort to secure information about their alleged roles in the theft of the PROMIS software. In dozens of interviews with those who came in contact with McDade and Buffam, Insight has pieced together the trail the Mounties blazed in the United States from coast to coast. Clearly, as they told others, they did not believe the official U.S. and Canadian reports and conclusions. And, McDade reportedly told people many officials in both governments had indeed lied, cheated and covered up a significant and dark story.

Insight has learned the two RCMP investigators plumbed the old Customs probe of Videnieks, the former DOJ official who was investigated for possible perjury. And what the Mounties found, according to some of those they interviewed, very well could confirm Riconosciuto’s claim that he knew Videnieks.

For example, months before McDade and Buffam came looking for answers in the United States, they had established a working relationship with John Belton, a Canadian living in Ontario who had become involved with PROMIS as a result of a 1980s securities-fraud scheme in Canada allegedly involving Earl Brian and companies he owned or controlled, such as Hadron Inc., Clinical Sciences Inc., Biotech Capital Corp. (renamed Infotechnology Corp. in 1987); and American Systology Inc. Belton’s securities-fraud claims resulted in a 1986 RCMP investigation and civil litigation that are ongoing today.

Belton, who met in person with the RCMP investigators at least 31 times and talked on the telephone with them dozens more, reportedly steered the Mounties to previously unknown information involving the Customs probe of Videnieks. And this led McDade to Scott Lawrence, the agent in Customs’ Boston office who was in charge of the investigation of Videnieks. What information Lawrence may have passed along to McDade is anyone’s guess, as neither Lawrence nor the Mountie will say. But Insight has confirmed Lawrence and McDade talked. And, based on documents obtained by Insight concerning the Customs probe, the investigation was wide-ranging in its subpoena request.

For example, according to a Nov. 15, 1993, letter to Justice Department Assistant Attorney General John Dwyer from Lawrence’s boss, John T. Kelly, Customs’ acting regional director in Boston: “Concerning the Peter Videnieks investigation, I believe that to properly complete this investigation, the assistance of federal grand juries in a number of locations will be required.” Locations of the requested grand juries included Seattle, the District of Columbia and the Northern District of Illinois. And the purpose of impaneling these grand juries was, according to the Kelly letter, to obtain testimony and documents from about 22 people connected to the Inslaw/ PROMIS affair, as well as the CIA and the Wackenhut Corp. How this tied in to a simple case of suspected perjury by Videnieks is unknown.

A former high-ranking federal law-enforcement official told Insight that “Videnieks was under investigation by an internal-affairs unit at the Customs Service and that the investigation, which included other matters, centered on an allegation that Videnieks committed perjury at the 1992 trial of Michael Riconosciuto.” According to this source, “Customs’ internal affairs ultimately dropped the probe because Videnieks no longer was an employee of the agency.”

This former official, who asked not to be identified, further said that Kelly and Lawrence had tried unsuccessfully to get a Boston-based U.S. attorney on the case but failed. Main Justice got involved because of its then-ongoing probe into Inslaw that Reno ordered. Kelly had hoped that main Justice would authorize the requested grand juries but, ultimately, he was told to seek authority elsewhere; impaneling the three grand juries would not be authorized by Washington. Finally, after many attempts, Customs dropped the case because Videnieks no longer worked for the agency.

To Jimmy Rothstein, a retired New York City policeman who worked with Kelly on the Videnieks matter, that’s not quite what happened. The investigation came to a dead end “right after Lawrence interviewed Alexander Haig,” Rothstein tells Insight. “I was sitting in an Irish pub in Boston with Tim Kelly,” he explains, “and we were waiting for the call from Lawrence. The thing got shut down. Tim Kelly responded by saying, `They ain’t gonna screw my guys over.’ Nothing ever came of it, though, and I told them this from the beginning.”

Why Haig, a former secretary of state, White House official and Army general would be interviewed as part of a Customs investigation could not be established. Haig couldn’t be reached for comment.

Videnieks long has denied any involvement with Riconosciuto or Earl Brian, or being involved in any conspiracy or illegal scheme to sell or convert the PROMIS software. In a brief telephone interview with Insight, Videnieks recently claimed that he couldn’t recall the specifics of the investigation by Customs but warned that Insight “had better get the story right or I’ll have my attorneys up to see you.”

Because Customs agents Lawrence and Kelly have declined Insight’s requests for interviews, it’s difficult to know the ins and outs of their probe, let alone what they found to prove or disprove the allegations of perjury. However, this much is clear: Videnieks’ denials never have been contradicted. And, as a result, this key portion of Riconosciuto’s claims remains in question. But, as Insight reported in Part II of this series, other Riconosciuto stories appear to have been confirmed by the RCMP investigators and by documentary evidence obtained by this magazine.

This may explain why the Mounties spent so much time on the portions of Riconosciuto’s claims involving Videnieks. If they could show the alleged links did exist, that might begin to unravel a string of deception that could lead to the highest levels of the U.S. and Canadian governments. Belton kept copious notes of the conversations he had with the RCMP investigators. In one such note, dated June 8, 2000, Belton wrote that McDade told him “the `Drug Tug’ captain Calvin Robinson was the Videnieks driver to the Cabazon – ties to Earl Brian and Michael Riconosciuto.”

This was followed by a June 16, 2000, notation about McDade informing Belton that “they [McDade and Buffam] have determined a second material definitive connection between Peter Videnieks and Michael Riconosciuto. i `Drug Tug’ captain Calvin Robinson – Videnieks has always denied an association with Michael Riconosciuto. I confirmed it, I can put Videnieks with Michael Riconosciuto now.”

The reference to the “Drug Tug” concerns the 1988 seizure of a barge hauling 157 tons of hashish and marijuana into San Francisco Bay. The skipper of the boat was Calvin Robinson, a man who long has maintained that he and his company were the victims of a government setup. According to Belton, “Sean told me that he interviewed Calvin Robinson and that Robinson was the driver for Peter Videnieks to the Cabazon Indian Reservation.”

This is about what McDade also told Inslaw’s Bill Hamilton in one of many conversations, also noted for the record. “McDade said that he could prove that Videnieks committed perjury when he testified against Riconosciuto, that he had interviewed the man who drove Videnieks to the reservation,” Hamilton recalls.

Then there’s Harry Martin, a journalist with 32 years of experience, publisher of the weekly Napa Sentinel and is a city councilman in that picturesque California township. He recently told Insight that, in the process of doing preliminary work on Riconosciuto years back, “I spoke to Peter Videnieks in either 1990 or 1991 – before Michael had been arrested -and Videnieks admitted that he knew Riconosciuto.” Martin also says that he spoke to Riconosciuto prior to the now-infamous March 1991 affidavit given to Inslaw outlining alleged illegal schemes and before the now-convicted felon was arrested on illegal drug charges.

Martin says he was interested but wanted to check out individuals Riconosciuto had mentioned he’d known to verify the man’s general veracity. “That’s how I got to Videnieks,” Martin says. “I just called the guy up and asked him if he knew Riconosciuto and he said yes, he did. That was before his [Riconosciuto’s] arrest.”

If accurate, this places Videnieks on a collision course with what he has testified under oath and in sworn statements to federal investigators. It also gives credence to one of the wilder aspects of another Riconosciuto story which the RCMP spent considerable time tracking down. Because Videnieks is a central player in the Hamiltons’ allegations that the DOJ stole their software, whether Videnieks did know Riconosciuto is key to connecting the two men to the Cabazon Indian reservation, where Riconosciuto claims to have modified the software.

If McDade’s statements to Belton and Hamilton are true and Martin’s recollections of his conversation with Videnieks are correct, it would appear the connection has been made. In turn, it could revamp not only the Inslaw case in the courts and in Congress, but it would raise complicated issues in Canada where the RCMP probe continues. When and how the Mounties’ investigation will end is a mystery. But this much is certain: It is having reverberations in security circles around the world.

To be continued.

Feb 19, 2001

By Kelly Patricia O Meara

The dejected officer shakes his head. “We got further than anyone else ever did on this case,” he says, “and nobody outside of law enforcement will ever know what we found because no one in law enforcement can ever tell anyone what we found.”

The speaker was talking about a case on which he had worked most of last year with Sean McDade and Randy Buffam, officers of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) who conducted an eight-month secret investigation in the United States in search of the truth about decades-old allegations concerning stolen software called PROMIS and its relation to suspected breaches in Canadian national security.

Insight carefully has tracked the Mounties’ ongoing investigation, code-named Project Abbreviation, a far-reaching international probe extending well beyond the theft of the breakthrough PROMIS computer software created in the late 1970s by Bill and Nancy Hamilton, owners of the firm Inslaw Inc.

As a former congressional investigator tells Insight, “There is a putrid stench that reaches across party lines [in Washington] and involves cover-ups by governments which have spent millions of dollars pretending to investigate the Inslaw affair only to end up with nothing to show for it. You don’t have to wonder why so many investigations failed; you only have to look at the evidence that shows there is more to the [alleged] theft of PROMIS than meets the eye. And powerful people don’t want it out.”

This also is what the RCMP investigators have told people interviewed by Insight about what the Mounties discovered as their probe quickly expanded from PROMIS to include a cast of characters engaged in or suspected of involvement in high-level espionage, organized crime, illegal-drug shipments, arms smuggling, murder and money laundering. In fact, McDade and Buffam are continuing to look at a case that has thwarted investigations by many others, including two congressional committees, the U.S. Justice Department, a special prosecutor, swarms of federal law-enforcement officers and prosecutors, a special commission in Canada and many journalists.

But until the RCMP probe got under way, investigators were unable to solve the myriad of riddles and conundrums surrounding the Inslaw matter. Many told Insight that as soon as anyone began to turn up answers about these shadowy figures and international intrigues, promising investigations suddenly were shut down on higher authority, witnesses disappeared and careers of experienced cops and seasoned federal prosecutors were ruined.

In the first three installments of this exclusive four-part investigative series, Insight tracked the Mounties and reported what they had said about their inquiries. We learned that the Mounties came to the United States in search of answers to two central questions. First, they wanted to confirm that it was Inslaw’s PROMIS software that Canada’s law-enforcement and intelligence agencies were using and, second, whether the software had been modified with backdoor access to facilitate secret espionage against Canada.

Because of the highly sensitive nature of such concerns, the RCMP investigators were careful not to make official contacts with government agencies in the United States, including those which years before had looked into the PROMIS caper. McDade and Buffam began by centering their investigation on people reportedly involved in the alleged theft of the computer software. Of great interest to the Mounties were the roles played by Peter Videnieks, a former U.S. Customs Service official on loan to the Justice Department in the 1980s who was accused of facilitating the theft of PROMIS, and Michael Riconosciuto, a computer genius convicted and jailed in an exotic drug case who claims to have been hired to put the backdoor in PROMIS for the purpose of international espionage and money laundering.

Although Canada long has denied having Inslaw software, and Videnieks has denied any involvement, the secret investigation by the Mounties was blessed from the highest levels of the RCMP and thousands of man-hours and great sums of money were expended to get to the bottom of what some see as a gravely serious breach of Canadian security. As with all of the other probes, this one started with PROMIS and, having discovered a shadowy network of bizarre criminal operations, branched out to include very serious allegations of wrongdoing beyond PROMIS. Details of these discoveries never were revealed in earlier public reports by Congress and the Justice Department. Yet there is proof positive that those probes delved into such areas and the American public was never told.

What appears to have made the RCMP probe different is that sources approached by the Mounties tipped Insight, leading to a cross-country investigation to determine why the national-security division of the RCMP was operating secretly in the United States and making inquiries about PROMIS and a series of international money-laundering schemes used by intelligence agencies and criminal enterprises.

Consider this item: In September last year, a thick plain manila envelope was sent by the RCMP to a California address. In it was a transcript of a recorded 1992 conversation between Riconosciuto and an FBI agent. Riconosciuto had been arrested but not yet convicted on drug charges and he was offering information to the FBI agent in exchange for admission to the bureau’s Witness Protection Program. The details contained in this transcribed tape recording were explosive.

The envelope had been sent for a specific reason to Cheri Seymour, a former journalist turned private detective whom McDade and Buffam had contacted six months earlier because of her work on stories about illegal-drug operations, gunrunning schemes and money laundering.

In the transcript of this tape-recorded phone call (one of several obtained by the RCMP and Insight), Riconosciuto offers the FBI information about bank accounts in the Cayman Islands and the Bahamas, at Castle Bank and Savings, and the Workers Bank in Colombia (Banco de la Troba Hadores) in which he claims to have “set up virtual dead drops.” Riconosciuto explains that this “is a way to get around reconciliations on ACH’s [automated clearinghouses],” an interbank network for electronic fund transfers.

The transcribed telephone conversation contains references to legal and illegal enterprises and a diverse cast of characters, including Robert Booth Nichols, a self-proclaimed CIA operative, licensed arms dealer and partner with Riconosciuto in a company called Meridian Arms, which was a weapons- development firm. The transcript also refers to Michael Abbell, a former Department of Justice official now serving time in a federal penitentiary for money laundering in connection with the Cali drug cartel.

In detailing these activities, Riconosciuto pulls no punches. In fact, many of the claims he makes to the FBI agent later are confirmed, often years before any had been publicly known, such as the Abbell matter and a DEA sting operation in Lebanon (see “The Plot Thickens in PROMIS Affair,” Feb. 5).

As far as Insight has been able to learn, the FBI never followed up on what Riconosciuto told their agent. One reason may have been that Riconosciuto had told similar stories to others in a desperate attempt to get out of prison but dared not provide corroborating evidence. Another reason may be that, prior to the RCMP probe, people fingered by Riconosciuto flatly denied his allegations or said they never had heard of him. But by tracking the Mounties and obtaining or reviewing originals or copies of much of the data they collected, Insight confirmed that the RCMP investigators found substantial evidence to confirm many of Riconosciuto’s claims. Much of this data had been overlooked by previous investigators, including documents and computer tapes secreted for years in storage and in a house trailer in the middle of Death Valley.

The transcript sent by the Mounties to Seymour takes on special significance because none of the information in it dealt with the alleged theft and modification of the PROMIS software. Or did it? Was the RCMP sending a cryptic message about a change in the focus of the RCMP investigation, or was it signaling Seymour that the PROMIS software was being used in the international banking system for illegal activities? If the latter is true, the Mounties aren’t the first investigators to run into the proposition that PROMIS has been manipulated for other nefarious purposes in addition to international espionage.

Take, for example, the 1992 House Judiciary Committee investigation of the Inslaw affair. John Cohen, one of the lead investigators on the committee, suspected that there was much more involved with the PROMIS case than a contract dispute or alleged software theft. His committee was conducting its hearings when Seymour and Cohen first got together; she was pursuing a story about illegal-drug trafficking and money laundering and wrote to him about her findings and possible links to the panel’s probe. “Cohen,” recalls Seymour, “was very much on top of this; he knew what was going on.”

The two investigators explored the idea that PROMIS was being used for illegal activities in the banking system. According to Seymour, Cohen “didn’t mince words. He told me that he had a theory about why PROMIS was taken and that it was because it could be modified to track money laundering -and that it therefore could be modified to control hundreds of accounts and move money invisibly through the international banking system.” Seymour further says that Cohen said “what a lot of people don’t realize is that there are two banking systems. There’s CHIPS and SWIFT, and the phrase `Swift Chips’ has been spread throughout this whole investigation without a lot of people realizing what that meant. Swift Chips is a referral to those two clearinghouse systems. They do $2 billion worth of banking transactions per day and, if one was able to move accounts through there [undetected], you could move money invisibly around the world.”

Notwithstanding that its chief investigator had pursued such theories during the panel’s investigation, in the end there was no mention of money laundering in the official report the Judiciary Committee issued on the Inslaw matter. Cohen tells Insight that the committee was “strictly focused on the Hamiltons’ allegations about the theft of their software. Drugs and money laundering certainly were topics, but it wasn’t part of what the committee reported. That type of information was collected as part of the information provided by people interviewed by the committee.” But it was never fully pursued, he says.

“Another area,” Cohen continues, “was this whole MCA element” that Riconosciuto had said was part of the larger PROMIS story. “We were able to support that Robert Booth Nichols had connections with organized crime because he was someone who was identified on a FBI wiretap. That investigation [of MCA] for some reason was shut down. We’re not talking about wackos; we’re talking about assistant U.S. attorneys and FBI agents who felt very strongly that the investigation was shut down because they started looking at the wrong people.”

Cohen is referring to the early 1980s FBI investigation of suspected drug trafficking by Nichols and Eugene Giaquinto, then-president of MCA Home Entertainment and a partner with Nichols in Meridian International Logistics – the parent company of Meridian Arms, in which Riconosciuto also was involved. Wiretaps had been placed by the FBI on selected phones which recorded Nichols, Giaquinto and many others speaking with or about reputed Mafia figures allegedly trying to move in on the movie industry. In transcripts of many of these wiretaps, which Insight has obtained, there are references to the FBI probe and how friends in Washington, including at the Justice Department, would see to it that nothing ultimately would happen. Learning of this no doubt alarmed the FBI and federal prosecutors.

One of these investigators was FBI agent Thomas Gates, the lead investigator on the MCA case. He was brought into the House Judiciary Committee’s investigation because of his knowledge of the circumstances surrounding the 1991 death of freelance journalist Danny Casolaro and information concerning Nichols, et al. Like that of the Mounties, Casolaro’s investigation focused on the theft of PROMIS software and grew to encompass other criminal activities, including drug trafficking and money laundering. One of Casolaro’s sources was Nichols and, according to telephone records from that time, Casolaro spent hundreds of hours speaking with the shadowy figure in the months leading up to the journalist’s death.

At the same time that Casolaro was using Nichols as a source, he also was in contact with FBI agent Gates, whose case ultimately was shut down.

Just days before his death, Casolaro allegedly was warned by Nichols to drop his investigation. Casolaro reportedly had learned of the connection between former Justice official Abbell and Nichols and their alleged links to the Cali drug cartel – information provided by Riconosciuto that, at least as related to Abbell, proved accurate. Days later, Casolaro was found dead in a hotel room in Martinsburg, W.Va., where his arms had been savagely slashed nearly a dozen times. The death was ruled a suicide; the material resulting from his investigation disappeared.

Another investigator who followed parallel paths was U.S. Customs agent Scott Lawrence. He was the lead investigator out of the Boston internal-affairs office looking into allegations that Peter Videnieks had committed perjury when he testified in the 1992 trial of Riconosciuto. Videnieks had been fingered by Riconosciuto as having facilitated the theft of PROMIS and of having visited Riconosciuto often at the Cabazon Indian reservation where Riconosciuto worked on his various technical projects. At the trial, however, Videnieks denied knowing Riconosciuto or having any dealings with anyone associated with him. Others called to testify also denied knowing Riconosciuto.

Despite the denials, Lawrence spent more than two years investigating Videnieks and interviewing many of the same characters who had been questioned by other investigators, including the Judiciary Committee. And, like those before him, Lawrence obtained much of the same information about the connection between Nichols, Abbell and the Cali drug cartel, and reportedly collected information that confirmed other Riconosciuto stories.

Among those Lawrence contacted was Seymour, to whom he confided details of his probe, such as that Nichols would be testifying in Los Angeles in a 1993 lawsuit he had filed against the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) for pulling the weapons licenses necessary for his work with Meridian Arms. At this trial Nichols stated under oath that he was a CIA operative and, according to news accounts of the trial, Nichols’ defense was that “he toiled quietly and selflessly for nearly two decades on behalf of the shadowy CIA keepers in more than 30 nations, from Central America to Southeast Asia.”

The Customs agent was so fixed on the claims made by Riconosciuto about Abbell, Nichols, Videnieks and others that he had Seymour give a statement under oath about her knowledge of the convicted felon’s claims. But Lawrence’s investigation came to a sudden end when the Justice Department declined a request to impanel several grand juries in the United States, including one in Seattle, to depose officials from the CIA. Videnieks never was charged with any wrongdoing. Officially, Insight was told, Customs shut down its probe because Videnieks no longer was an employee of the service. And Videnieks tells Insight that he did nothing wrong, but can’t remember much from that time.

Although Insight made repeated attempts to speak with Lawrence and his then-supervisor, John (Tim) Kelly, neither agent would provide details of their investigation. Lawrence did say during a brief telephone conversation that “it’s a good thing that you’re working on this; it’s a good thing to follow.” RCMP investigators must have thought so, too, since they tracked down Lawrence, who now is working in California, and obtained valuable assistance from him, Insight has been told.