My friend 007 Super Spook Otis Johnson was directly involved with raising the sunken Russian Nuclear SUB.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4PWpFRHTRjE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LQV3LcTMAis

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XOW4V-yrlh0

Raising Sunken Ships

http://www.pbs.org/saf/1305/features/ship2.htm

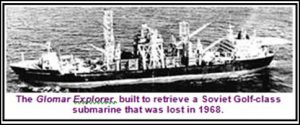

The Glomar Explorer

In 1968, a flurry of coded communications alerted the U.S. Navy to the loss of a Soviet Golf-class submarine, an older diesel vessel that had sunk in 17,000 feet of water about 750 miles northwest of Hawaii. U.S. Intelligence reports soon revealed that an explosion had occurred, probably while the sub was at the surface, but that it was mostly intact – and that it still carried nuclear missiles on board. A few years later the wealthy eccentric Howard Hughes constructed the Glomar Explorer, an enormous barge built for the ostensible purpose of mining manganese nodules from the ocean floor. Although manganese nodules are real, the mining venture was actually an elaborate hoax.

In reality, the Glomar Explorer was built as part of an audacious CIA effort to retrieve the Golf. Codenamed “Project Jennifer,” the plan was to use a giant claw dangling on the end of a three-mile-long tether to grasp the submarine and raise it into a “moon pool” – a large area open to the sea – built inside the Glomar Explorer. The submarine would then be searched for Soviet codebooks, communications gear, and nuclear warheads.

The retrieval, begun in 1974, did not go smoothly. Trouble began when the claw (nicknamed “Clementine” by the crew) had been lowered almost within reach of the wreck of the Golf. While tantalizingly close to the submarine, the operators lost control, and the claw collided violently with the seabed. Inspection by remote camera showed no visible damage to the claw assembly, however, so the engineers decided to continue with the operation. The claw was lowered the final few feet, and found purchase around the hull of the wreck. The slow, methodical process of bringing the Golf to the surface began, and the success of the salvage effort was apparently in sight, despite the earlier mistake.

Hours later, when the submarine was about two miles below the surface, disaster struck. The impact of Clementine with the ocean bottom had seriously weakened the claw assembly. Three of the five tines that carried the load in the claw suddenly broke off, leaving most of the 5000-ton Golf unsupported. Unable to take the strain, the submarine tore apart under its own weight, most of it plunging back into the depths – but not before spilling a missile from an open missile bay.

Tense moments passed onboard the Glomar Explorer, as the crew steeled themselves for the nuclear explosion that many expected when the lost warhead smashed into the ocean floor. The explosion never came. Only a small part of the forward section of the submarine that remained in the grasp of the claw could be brought to the surface. This section contained little of interest to the CIA, but found among the wreckage were the remains of six Soviet sailors. They were given a solemn burial at sea by the crew of the Glomar Explorer, the ceremony performed in Russian.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GSF_Explorer

GSF Explorer

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Career | |

| Name: | GSF Explorer |

| Owner: | Transocean |

| Operator: | Transocean |

| Port of registry: | Vanuatu, Port Vila |

| Builder: | Sun Shipbuilding & Drydock Co. Chester, Pennsylvania |

| Cost: | $350 million + |

| Laid down: | 1971 |

| Launched: | 04 November 1972 |

| Completed: | 31 July 1998 |

| Acquired: | 2010 |

| Identification: | ABS class no: 7310452 Call sign: YJQQ3 DNV ID:29748 IMO number: 7233292 MMSI no.:576830000 |

| Status: | Operational |

| Notes: | [1] |

| Career (USA) | |

| Name: | Hughes Glomar Explorer |

| Namesake: | Howard Hughes |

| Builder: | Sun Shipbuilding and Drydock Co. |

| Launched: | 04 November 1972 |

| In service: | 01 July 1973 |

| Fate: | Leased (not SAP) |

| Notes: | [1] |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Drillship |

| Displacement: | 50,500 long tons (51,310 t) light |

| Length: | 619 ft (189 m) |

| Beam: | 116 ft (35 m) |

| Draft: | 38 ft (12 m) |

| Propulsion: | Diesel-electric 5 × Nordberg 16-cylinder diesel engines driving 4,160 V AC generators turning 6 × 2,200 hp (1.6 MW) DC shaft motors, twin shafts |

| Speed: | 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 160 |

| Notes: | [1] |

GSF Explorer, formerly USNS Hughes Glomar Explorer (T-AG-193), is a deep-sea drillship platform initially built for the United States Central Intelligence Agency Special Activities Division secret operation Project Azorian to recover the sunken Soviet submarine K-129, lost in April 1968.[2][3]

The cultural impact of Glomar Explorer is indicated by its reference in a number of books: The Ghost from the Grand Banks, a 1990 science fiction novel by Arthur C. Clarke; Shock Wave by Clive Cussler; Charles Stross‘s novel, The Jennifer Morgue; and The Hunt for Red October by Tom Clancy.

Contents

Construction

Hughes Glomar Explorer (HGE), as the ship was called at the time, was built between 1973 and 1974, by Sun Shipbuilding and Drydock Co. for more than US$350 million at the direction of Howard Hughes for use by his company, Global Marine Development Inc.[4] This is equivalent to $1.67 billion in present-day terms.[5] She set sail on 20 June 1974. Hughes told the media that the ship’s purpose was to extract manganese nodules from the ocean floor. This marine geology cover story became surprisingly influential, spurring many others to examine the idea. But in sworn testimony in United States district court proceedings and in appearances before government agencies, Global Marine executives and others associated with Hughes Glomar Explorer project unanimously maintained that the ship could not be used in any economically viable ocean mineral operation.

Project Azorian

Main article: Project Azorian

Because K-129 sank in very deep water, at a depth of 3.0 miles (4.8 km), located 1,560 miles (2,510 km) NW of Hawaii,[6] a large ship was required for the recovery operation. Such a vessel would easily be spotted by Soviet vessels, which might then interfere with the operation, so an elaborate cover story was developed. The CIA contacted Hughes, who agreed to assist.[7]

While the ship did recover a portion of K-129, a mechanical failure in the grapple caused two-thirds of the recovered section to break off during recovery.[8] This lost section is said to have held many of the most sought items, including the code book and nuclear missiles. It was subsequently reported two nuclear-tipped torpedoes and some cryptographic machines were recovered, along with the bodies of six Soviet submariners, who were given a formal, filmed burial at sea.[9]

The operation became public in February 1975 when the Los Angeles Times published a story about “Project Jennifer”, followed by news stories with additional details in other publications, including The New York Times. The CIA, wanting to neither confirm nor deny the story, issued the Glomar response, which set the precedent for subsequent boilerplate responses to Freedom of Information Act requests.[10] The true name of the project was not publicly known to be Project Azorian until 2010.

Red Star Rogue (2005) by Kenneth Sewell makes the claim “Project Jennifer” recovered virtually all of K-129 from the ocean floor.[11][12] Sewell states, “[D]espite an elaborate cover-up and the eventual claim that Project Jennifer had been a failure, most of K-129 and the remains of the crew were, in fact, raised from the bottom of the Pacific and brought into the Glomar Explorer“.[N 1] A subsequent film and book by Michael White and Norman Polmar revealed testimony from on-site crewmen as well as B&W video of the actual recovery operation. These sources indicate that only the forward 38 feet of the submarine were recovered.

After Project Azorian

Mothballing

Glomar Explorer mothballed in Suisun Bay, California, in June 1993

While the ship had an enormous lifting capacity, there was little interest in operating the vessel because of her high cost. From March to June 1976, the General Services Administration (GSA) published advertisements inviting businesses to submit proposals for leasing the ship.[14] By the end of four months, GSA had received a total of seven bids, including a US$2 million offer submitted by a Lincoln, Nebraska college student, and a US$1.98 million offer from a man who said he planned to seek a government contract to salvage the nuclear reactors of two United States submarines. These are equivalent to $8.29 million and $8.21 million in present-day terms, respectively.[5] The Lockheed Missile and Space Company submitted a US$3 million, two-year lease proposal contingent upon the company’s ability to secure financing. GSA had already extended the bid deadline twice to allow Lockheed to find financial backers for its project without success and the agency concluded there was no reason to believe this would change in the near future.

Although the scientific community rallied to the defense of Hughes Glomar Explorer, urging the president to maintain the ship as a national asset, no agency or department of the government wanted to assume the maintenance and operating cost.[15] Subsequently, in September 1976, the GSA turned Hughes Glomar Explorer over to the Navy for mothballing, and in January 1977, after she was prepared for dry docking at a cost of more than two million dollars, the ship became part of the Navy’s Suisun Bay Reserve Fleet.[16]

Lease, sale and current status

In September 1978, Ocean Minerals Company consortium of Mountain View, California announced it had leased Hughes Glomar Explorer and that in November would begin testing a prototype deepsea mining system in the Pacific Ocean. The consortium included subsidiaries of the Standard Oil Company of Indiana, Royal Dutch Shell, and Boskalis Westminster Group NV of the Netherlands. Another partner, and the prime contractor, was the Lockheed Missiles and Space Company.

In 1997, the ship was taken to Atlantic Marine’s Mobile, Ala shipyard for modifications that converted her to a dynamically-positioned deep sea drilling ship, capable of drilling in waters of 7,500 feet (2,300 m) and, with some modification, up to 11,500 feet (3,500 m), which is 2,000 feet (610 m) deeper than any other existing rig. The conversion cost over $180 million US and was completed during the first quarter of 1998. This is equivalent to $260 million in present-day terms.[5]

The conversion of the vessel from 1996-1998 was the start of a 30-year lease from the U.S. Navy to Global Marine Drilling at a cost of US$1 million per year. Global Marine merged with Santa Fe International Corporation in 2001 to become GlobalSantaFe Corporation, which merged with Transocean Inc. in November 2007 and operates the vessel as GSF Explorer.

In 2010, Transocean acquired the vessel in return for a US$15 million cash payment.[17]

After finishing up a contract for ONGC in India in late 2014, the GSF Explorer is currently idle in Brunei Bay off the island of Labuan.

The rig was reflagged from Houston, US to Port Vila, Vanuatu in the 3rd quarter of 2013.[18]

See also

- Not to be confused with Glomar Challenger, “the first research vessel specifically designed in the late 1960s for the purpose of drilling into and taking core samples from the deep ocean floor.”[19]

- Hughes Mining Barge

- Special Activities Division

References

Notes

- Minutes of the Sixth Plenary Session, USRJC, Moscow, 31 August 1993.[13]

Citations

- “ABS Record: GSF Explorer.” American Bureau of Shipping, 2010. Retrieved: 25 December 2010.

- · Burleson 1997, p. 52.

- · “Mysteries of the Deep: Raising Sunken Ships: The Glomar Explorer.” Scientific American Frontiers (PBS), p. 2. Retrieved: 25 December 2010.

- · Snieckus, Darius. “…and another thing… An offshore Hughes who… “ OilOnline, 1 November 2001. Retrieved: 25 December 2010.

- · Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–2014. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- · GWU National Security Archive

- · Phelan, James. “An Easy Burglary Led to the Disclosure of Hughes-C.I.A. Plan to Salvage Soviet Sub”. The New York Times, 27 March 1975, p. 18.

- · Sontag et al. 1998, p. 196.

- · Sontag et al. 1998, p. 277.

- · “Neither Confirm Nor Deny”. Radiolab. Radiolab, WNYC. 12 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- · Sewell 2005, pp. 128, 148.

- · Podvig 2001, p. 243.

- · Sewell 2005, pp. 131, 261.

- · “Notice of Availability for Donation of the Test Craft Ex-Sea Shadow (IX-529) and Hughes Mining Barge (HMB-1).” Federal Register, Volume 71, Number 178, 14 September 2006, p. 54276.

- · Toppan, Andrew. “The Hughes Glomar Explorer’s Mission.” the-kgb.com. Retrieved: 25 December 2010.

- · Pike, John. “Project Jennifer: Hughes Glomar Explorer.” Intelligence Resource Program via fas.org, 16 February 2010. Retrieved: 25 December 2010.

- · “Transocean 10Q SEC Filing on 4 August 2010.”brand.edgar-online.com. Retrieved: 25 December 2010.

- · [1]rigzone.com Retrieved: 17 December 2013.

- Watson, Jim. “USGS.” usgs.gov, 5 May 1999. Retrieved: 25 December 2010.

- Sharp, David (2012). The CIA’s Greatest Covert Operation: Inside the Daring Mission to Recover a Nuclear-Armed Soviet Sub. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-7006-1834-7.Bibliography

- Burleson, Clyde W. The Jennifer Project. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8909-676-4.

- DeLuca, Marshall and William Furlow, eds. “Steeped in history, Glomar Explorer finally returns to industry, Converted vessel set to drill in record water depth.” Offshore magazine, Volume 58, Issue 3, March 1998.

- Dunham, Roger C. Spy Sub: Top Secret Mission To The Bottom Of The Pacific. New York: Penguin Books, 1996. ISBN 0-451-40797-0.

- Podvig, Pavel, ed. Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces. Stanford, CA: Stanford University, 2001. ISBN 0-262-16202-4. (originally published by Center for Arms Control Studies, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology)

- Polmar, Norman & Michael White. PROJECT AZORIAN-The CIA and the Raising of the K-129. Naval Institute Press. 2010. ISBN 978-1-59114-690-2.

- Sewell, Kenneth. Red Star Rogue: The Untold Story of a Soviet Submarine’s Nuclear Strike Attempt on the U.S. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. ISBN 0-7432-6112-7.

- Sontag, Sherry, Christopher Drew with Annette Lawrence Drew. Blind Man’s Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage. New York: Harper, 1998. ISBN 0-06-103004-X.

- Varner, Roy and Wayne Collier. A Matter of Risk: The Incredible Inside Story of the CIA’s Hughes Glomar Explorer Mission to Raise a Russian Submarine. New York: Random House, 1978. ISBN 0-394-42432-

-

Special Activities Division

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- The Special Activities Division (SAD) is a division in the United States Central Intelligence Agency‘s (CIA) National Clandestine Service (NCS) responsible for covert operations known as “special activities”. Within SAD there are two separate groups, SAD/SOG for tactical paramilitary operations and SAD/PAG for covert political action.[1]. The Special Activities Division reports directly to the Deputy Director of the National Clandestine Service.

Special Operations Group (SOG) is the department within SAD responsible for operations that include the collection of intelligence in hostile countries and regions, and all high threat military or intelligence operations with which the U.S. government does not wish to be overtly associated.[2] As such, members of the unit (called Paramilitary Operations Officers and Specialized Skills Officers) normally do not carry any objects or clothing (e.g., military uniforms) that would associate them with the United States government.[3] If they are compromised during a mission, the United States government may deny all knowledge.[4]

SOG is generally considered the most secretive special operations force in the United States. The group selects operatives from other tier one special mission units such as Delta Force, DEVGRU and ISA, as well as other United States special operations forces, such as USNSWC, MARSOC, USASF and 24th STS.

SOG Paramilitary Operations Officers account for a majority of Distinguished Intelligence Cross and Intelligence Star recipients during any given conflict or incident which elicits CIA involvement. An award bestowing either of these citations represents the highest honors awarded within the CIA organization in recognition of distinguished valor and excellence in the line of duty. SAD/SOG operatives also account for the majority of the names displayed on the Memorial Wall at CIA headquarters indicating that the agent died while on active duty.[5]

Political Action Group (PAG) is responsible for covert activities related to political influence, psychological operations and economic warfare. The rapid development of technology has added cyberwarfare to their mission. Tactical units within SAD are also capable of carrying out covert political action while deployed in hostile and austere environments. A large covert operation usually has components that involve many, or all, of these categories, as well as paramilitary operations. Political and Influence covert operations are used to support U.S. foreign policy. Often overt support for one element of an insurgency would be counter-productive due to the impression it would have on the local population. In such cases, covert assistance allows the U.S. to assist without damaging these elements in the process. Many of the other activities (such as propaganda, economic and cyber) support the overall political effort. There have been issues in the past with attempts to influence the US media such as in Operation Mockingbird. However, these activities are now subject to the same oversight as all covert action operations.[6]

-

Overview

SAD provides the President of the United States with an option when covert military and/or diplomatic actions are not viable or politically feasible. SAD can be directly tasked by the President of the United States or the National Security Council at the President’s direction. This is unlike any other U.S. special mission force. However, SAD/SOG has far fewer members than most of the other special missions units, such as the U.S. Army’s 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (Delta Force) or Naval Special Warfare Development Group (DEVGRU).[7][8][9]

As the action arm of the NCS, SAD/SOG conducts direct action missions such as raids, ambushes, sabotage, targeted killings[10][11][12] and unconventional warfare (e.g., training and leading guerrilla and military units of other countries in combat). SAD/SOG also conducts special reconnaissance, that can be either military or intelligence driven, but is carried out by Paramilitary Officers (also called Paramilitary Operatives) when in “non-permissive environments“. Paramilitary Operations Officers are also fully trained case officers (i.e., “spies”) and as such conduct clandestine human intelligence (HUMINT) operations throughout the world.[13] SAD/SOG officers are selected from the most elite U.S. military units.[9]

The political action group within SAD conducts the deniable psychological operations, also known as black propaganda, as well as “Covert Influence” to effect political change as an important part of any Administration’s foreign policy.[1] Covert intervention in a foreign election is the most significant form of political action. This could involve financial support for favored candidates, media guidance, technical support for public relations, get-out-the-vote or political organizing efforts, legal expertise, advertising campaigns, assistance with poll-watching, and other means of direct action. Policy decisions could be influenced by assets, such as subversion of officials of the country, to make decisions in their official capacity that are in the furtherance of U.S. policy aims. In addition, mechanisms for forming and developing opinions involve the covert use of propaganda.[14]

Propaganda includes leaflets, newspapers, magazines, books, radio, and television, all of which are geared to convey the U.S. message appropriate to the region. These techniques have expanded to cover the internet as well. They may employ officers to work as journalists, recruit agents of influence, operate media platforms, plant certain stories or information in places it is hoped it will come to public attention, or seek to deny and/or discredit information that is public knowledge. In all such propaganda efforts, “black” operations denote those in which the audience is to be kept ignorant of the source; “white” efforts are those in which the originator openly acknowledges himself; and “gray” operations are those in which the source is partly but not fully acknowledged.[14][15]

Some examples of political action programs were the prevention of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) from winning elections between 1948 and the late 1960s; overthrowing the governments of Iran in 1953, and Guatemala in 1954; arming rebels in Indonesia in 1957; and providing funds and support to the trade union federation Solidarity following the imposition of martial law in Poland after 1981.[16]

SAD’s existence became better known as a result of the “Global War on Terror“. Beginning in autumn of 2001, SAD/SOG paramilitary teams arrived in Afghanistan to hunt down al-Qaeda leaders, facilitate the entry of U.S. Army Special Forces and lead the United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan against the ruling Taliban. SAD/SOG units also defeated Ansar al-Islam in Iraqi Kurdistan prior to the invasion of Iraq in 2003[17][18] and trained, equipped, organized and led the Kurdish peshmerga forces to defeat the Iraqi army in northern Iraq.[13][17] Despite being the most covert unit in U.S. Special Operations, numerous books have been published on the exploits of CIA paramilitary officers, including Conboy and Morrison’s Feet to the Fire: CIA Covert Operations in Indonesia,[19] and Warner’s Shooting at the Moon: The Story of America’s Clandestine War in Laos.[20] Most experts consider SAD/SOG the premiere force for unconventional warfare (UW), whether that warfare consists of either creating or combating an insurgency in a foreign country.[7][21][22]

- There remains some conflict between the National Clandestine Service and the more clandestine parts of the United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM),[23] such as the Joint Special Operations Command. This is usually confined to the civilian/political heads of the respective Department/Agency. The combination of SAD and USSOCOM units has resulted in some of the most notable successes of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, to include the locating and killing of Osama bin Laden.[22][24] SAD/SOG has several missions. One of these missions is the recruiting, training, and leading of indigenous forces in combat operations.[22] SAD/SOG and its successors have been used when it was considered desirable to have plausible deniability about U.S. support (this is called a covert operation or “covert action”).[13] Unlike other special missions units, SAD/SOG operatives combine special operations and clandestine intelligence capabilities in one individual.[9] These individuals can operate in any environment (sea, air or ground) with limited to no support.[7]

Covert action

- Under U.S. law, the CIA is authorized to collect intelligence, conduct counterintelligence and to conduct covert action by the National Security Act of 1947.[1] President Ronald Reagan issued Executive Order 12333 titled “United States Intelligence Activities” in 1984. This order defined covert action as “special activities,” both political and military, that the U.S. government would deny, granting such operations exclusively to the CIA. The CIA was also designated as the sole authority under the 1991 Intelligence Authorization Act and mirrored in Title 50 of the United States Code Section 413(e).[1][22] The CIA must have a presidential finding issued by the President of the United States in order to conduct these activities under the Hughes-Ryan amendment to the 1991 Intelligence Authorization Act.[25] These findings are then monitored by the oversight committees in both the U.S. Senate, called the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) and the U.S. House of Representatives, called the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI).[26]

Every U.S. President since George Washington has used covert action as a part of their broader foreign policy, whether Republican or Democratic, liberal or conservative.[27] The majority of these covert action operations were successful.[28] Most of the operations that were not successful were directed by the President over the objections of the CIA.[28] Some of the most controversial “covert action” programs, such as the Iran–Contra affair, were not primarily the work of the CIA.[29] Covert action programs are also much less expensive than overt political or military actions.[1] The Pentagon commissioned a study to determine whether the CIA or the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) should conduct covert action paramilitary operations. Their study determined that the CIA should maintain this capability and be the “sole government agency conducting covert action.” The DoD found that, even under U.S. law, it does not have the legal authority to conduct covert action, nor the operational agility to carry out these types of missions.[30] The operation in May 2011 that resulted in the death of Osama bin Laden was a covert action under the authority of the CIA.[24][31]

Selection and training

- SAD/SOG has several hundred officers, mostly former members of special operations forces (SOF) and a majority from the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC).[32] The CIA has also recruited individuals within the agency.[33] The CIA’s formal position for these individuals is “Paramilitary Operations Officers” and “Specialized Skills Officers.” Paramilitary Operations Officers attend the Clandestine Service Trainee (CST) program, which trains them as clandestine intelligence operatives (known as “Core Collectors” within the Agency). The primary strengths of SAD/SOG Paramilitary Officers are operational agility, adaptability, and deniability. They often operate in small teams, typically made up of six operators (with some operations being carried out by a single officer), all with extensive military special operations expertise and a set of specialized skills that does not exist in any other unit.[9] As fully trained intelligence case officers, Paramilitary Operations Officers possess all the clandestine skills to collect human intelligence—and most importantly—to recruit assets from among the indigenous troops receiving their training. These officers often operate in remote locations behind enemy lines to carry out direct action (including raids and sabotage), counter-intelligence, guerrilla/ unconventional warfare, counter-terrorism, and hostage rescue missions, in addition to being able to conduct espionage via HUMINT assets.

There are four principal elements within SAD’s Special Operations Group: the Air Branch, the Maritime Branch, the Ground Branch, and the Armor and Special Programs Branch. The Armor and Special Programs Branch is charged with development, testing, and covert procurement of new personnel and vehicular armor and maintenance of stockpiles of ordnance and weapons systems used by SOG, almost all of which must be obtained from clandestine sources abroad, in order to provide SOG operatives and their foreign trainees with plausible deniability in accordance with U.S. Congressional directives.

Together, SAD/SOG contains a complete combined arms covert military. Paramilitary Operations Officers are the core of each branch and routinely move between the branches to gain expertise in all aspects of SOG.[33] As such, Paramilitary Operations Officers are trained to operate in a multitude of environments. Because these officers are taken from the most highly trained units in the U.S. military and then provided with extensive additional training to become CIA clandestine intelligence officers, many U.S. security experts assess them as the most elite of the U.S. special missions units.[34]

SAD, like most of the CIA, requires a bachelor’s degree to be considered for employment. Many have advanced degrees such as Master’s and law degrees.[35] Many candidates come from notable schools, many from Ivy League institutions and United States Service Academies, but the majority of recruits today come from middle-class backgrounds.[36] SAD officers are trained at Camp Peary, Virginia (also known as “The Farm”) and at privately owned training centers around the United States. They also train its personnel at “The Point” (Harvey Point), a facility outside of Hertford, North Carolina.[37][38] In addition to the eighteen months of training in the Clandestine Service Trainee (CST) Program[39] required to become a clandestine intelligence officer, Paramilitary Operations Officers are trained to a high level of proficiency in the use and tactical employment of an unusually wide degree of modern weaponry, explosive devices and firearms (foreign and domestic), hand to hand combat, high performance/tactical driving (on and off road), apprehension avoidance (including picking handcuffs and escaping from confinement), improvised explosive devices, cyberwarfare, covert channels, Military Free Fall parachuting, combat and commercial SCUBA and closed circuit diving, proficiency in foreign languages, surreptitious entry operations (picking or otherwise bypassing locks), vehicle hot-wiring, Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE), extreme survival and wilderness training, combat EMS medical training, tactical communications, and tracking.

- While the World War II Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was technically a military agency under the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in practice it was fairly autonomous of military control and enjoyed direct access to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Major General William Joseph Donovan was the head of the OSS. Donovan was a soldier and Medal of Honor recipient from World War I. He was also a lawyer and former classmate of FDR at Columbia Law School.[40] Like its successor, the CIA, OSS included both human intelligence functions and special operations paramilitary functions. Its Secret Intelligence division was responsible for espionage, while its Jedburgh teams, a joint U.S.-UK-French unit, were forerunners of groups that create guerrilla units, such as the U.S. Army Special Forces and the CIA. OSS’ Operational Groups were larger U.S. units that carried out direct action behind enemy lines. Even during World War II, the idea of intelligence and special operations units not under strict military control was controversial. OSS operated primarily in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) and to some extent in the China-Burma-India Theater, while General of the Army Douglas MacArthur was extremely reluctant to have any OSS personnel within his area of operations.

From 1943 to 1945, the OSS also played a major role in training Kuomintang troops in China and Burma, and recruited other indigenous irregular forces for sabotage as well as guides for Allied forces in Burma fighting the Japanese army. OSS also helped arm, train and supply resistance movements, including Mao Zedong‘s People’s Liberation Army in China and the Viet Minh in French Indochina, in areas occupied by the Axis powers. Other functions of the OSS included the use of propaganda, espionage, subversion, and post-war planning.

One of the OSS’ greatest accomplishments during World War II was its penetration of Nazi Germany by OSS operatives. The OSS was responsible for training German and Austrian commandos for missions inside Nazi Germany. Some of these agents included exiled communists and socialist party members, labor activists, anti-Nazi POWs, and German and Jewish refugees. At the height of its influence during World War II, the OSS employed almost 24,000 people.[41]

OSS Paramilitary Officers parachuted into many countries then behind enemy lines, including France, Norway, Greece and The Netherlands. In Crete, OSS paramilitary officers linked up with, equipped and fought alongside Greek resistance forces against the Axis occupation.

OSS was disbanded shortly after World War II, with its intelligence analysis functions moving temporarily into the U.S. Department of State. Espionage and counterintelligence went into military units, while paramilitary and related functions went into an assortment of ‘ad hoc’ groups, such as the Office of Policy Coordination. Between the original creation of the CIA by the National Security Act of 1947 and various mergers and reorganizations through 1952, the wartime OSS functions generally went into CIA. The mission of training and leading guerrillas generally stayed in the United States Army Special Forces, but those missions required to remain covert were folded into the paramilitary arm of the CIA. The direct descendant of the OSS’ Special Operations is the CIA’s Special Activities Division.

- The Bay of Pigs Invasion (known as “La Batalla de Girón”, or “Playa Girón” in Cuba), was an unsuccessful attempt by a U.S.-trained force of Cuban exiles to invade southern Cuba and overthrow the Cuban government of Fidel Castro. The plan was launched in April 1961, less than three months after John F. Kennedy assumed the presidency of the United States. The Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces, trained and equipped by Eastern Bloc nations, defeated the exile-combatants in three days.

The sea-borne invasion force landed on April 17, and fighting lasted until April 19, 1961. CIA Paramilitary Operations Officers Grayston Lynch and William “Rip” Robertson led the first assault on the beaches, and supervised the amphibious landings.[48] Four American aircrew instructors from Alabama Air National Guard were killed while flying attack sorties.[48] Various sources estimate Cuban Army casualties (killed or injured) to be in the thousands (between 2,000 and 5,000).[49] This invasion followed the successful overthrow by the CIA of the Mosaddeq government in Iran in 1953[50] and Arbenz government in Guatemala in 1954,[51] but was a failure both militarily and politically.[52] Deteriorating Cuban-American relations were made worse by the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

.jpg)